Cardinal Wuerl Meets 'American Horror Story'

My best wishes to the surviving family of Rose Siggins

This feels like an appropriate story to tell near Halloween. Rod Dreher has struggled with the problem of reporting on clerical abuse, and it played a role in his departure from the Church. In my case, I had trouble getting this one published.

If you’re into this kind of television, you may recall the season of American Horror Story that focused on carnies. It’s one of two seasons I actually watched. I watched the one that was clearly a send-up of Trump and the alt-right too, because one of my guilty pleasures is shows that reflect the distance between cosseted Hollywood writers and the actual conservatives I know. But the Freakshow season was interesting.

One thing about carnival people is that you shouldn’t mess with them. They have hard lives, and it’s something I’m superstitious about.

A variety of things conspired to prevent my telling this story at the time. For one, I was newly Catholic when I was looking into this stuff. I’m a curious person, and part of that involved reading up on the ordinary of my hometown. For another, by the time it got to be truly serious, the PA grand jury report came out and Cardinal Wuerl resigned. And third, I’m not aware of how the situation has resolved. Things have obviously been somewhat busy since. But this is worth talking about, it’s a very strange and very dark case.

I want to be clear that I think all clerical abuse deserves to be investigated, and if found to be real, prosecuted to the full extent of the law. What this case demonstrates is some of the drawbacks of the eagerness to settle showed by some bishops. I would argue, in some cases, this may not be a judicious use of funds, at a minimum.

Donald Cardinal Wuerl was the longtime Archbishop of Washington, and hard as it may be to believe now, he actually enjoyed a reputation for being tough on clerical abuse. He earned that reputation largely because of his actions in the Fr. Anthony Cipolla case. By the very approach that Wuerl was credited with pioneering—turning accused priests over to civil authorities—Cipolla was, for all intents and purposes, not guilty.

Cipolla was accused by a man named Tim Bendig of abuse, after Bendig had been kicked out of the seminary. That abuse was never prosecuted criminally, though he was interviewed by DAs. There was no evidence for it. But Wuerl settled with the man—and he was a man, being 18 at the time—and removed Cipolla from ministry.

This was actually against his rights as a priest. Cipolla appealed his removal from ministry all the way to the Signatura, which ordered him reinstated in March 1993. The court reversed its decision in 1995 and upheld Cipolla’s removal from ministry—notably not on the grounds that he molested anyone, but because he was depressed and possibly suicidal—and in 2002 he was laicized by Pope John Paul II.

Wuerl resisted the initial reinstatement, and since bishops are more or less sovereign in their own dioceses, there wasn’t much to be done. Wuerl’s stand there earned him his reputation for toughness—here was a bishop who refused to reinstate an abuser, after the big bad Vatican was trying to impose one on the faithful of Pittsburgh.

The problem with that is that he was never established to be an abuser by any court, either a Church one or civil or criminal.

It’s worth noting that even SNAP—the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests—seemed to have doubts about this story. David Clohessy once wrote that Wuerl, “is using Mr. Bendig for his own selfish reasons: to try and protect bishops’ reputations.” I think that’s probably right.

One priest who came to his aid and said he should defend his rights, Father Alfred Kunz, was murdered during this time—a murder that’s never been solved. Kunz was tied in with a lot of traditionalist groups.

Thereafter, Bendig became a reliable source of quotes defending Cardinal Wuerl. There are articles in the Pittsburgh press about Bendig’s alleged abuse, and Wuerl got a major media cycle out of apologizing to the guy. Here’s one of the quotes:

“I’m thankful that Cardinal Wuerl has spoken out on my behalf. When you Google yourself and see all these posts calling you a liar, it feels like no one has ever believed you,” Bendig said.

“For all these years I have loved the Catholic faith even though the flashbacks made it impossible for me to set foot in a church. Pope Francis has made me feel like I can return, and the cardinal’s words have opened the door,” Bendig said. “I have always admired the way that Cardinal Wuerl took a stand against abusers. My hope is that, in the future, I can work with the church to get the message out about child protection.”

It’s worth noting that before and during this, there were much more well-documented instances of abuse which Wuerl didn’t handle well, like the cases of Frs. Zula, Pucci and Wolk, who were charged by the Allegheny County DA in 1988. And I don’t really see Bendig showing any attention to that in his public statements.

Bendig became, after a while, a publicist booking various voice actors, child stars and C-listers on the comic-cons-and-state-fairs circuit. Some of his clients were the voice of Big Bird, the voice of Courage the Cowardly Dog, the Soup Nazi from Seinfeld, and, as it happened, the cast of that season of American Horror Story.

This doesn’t seem to have been done on an exclusive basis, like a typical Hollywood agent. Naomi Grossman, one of Siggins’ castmates, explained that to me.

Larry Thomas, of Soup Nazi fame, told me, “I once got contacted by Tim Bendig over F.B. and he claimed to be friends with some of my friends, and he asked if he found me autograph shows could he rep me. I said sure, I'm not exclusive to anyone, so if you find me a show and the terms are acceptable you can. He has never found me one so I don't consider myself one of his clients. I only met him once at the Steel City Con but he didn't bring me in.”

After I had made a number of these calls, Bendig threatened to sue me.

This was about 2015. And as I was keeping an eye on all this, Rose Siggins died, on the Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Siggins played “Legless Suzie,” in that season, scooting around on a skateboard. In real life she seems like she was a pretty incredible woman. Despite her disability she managed to become a mechanic—I guess if you’re already on a skateboard it’s easy to get under cars—and raise two kids.

A GoFundMe appeared, first while she was in the hospital and then after she died, and it raised around $30,000. Bendig was behind it, and when I first noticed it, I suspected there would be problems. The change in purpose—first for her hospital bills, then for the funeral and to give something to the kids—was a problem. But the biggest problem was that he and the man the government considers his husband were soliciting donations directly to their house in Pittsburgh. I’ll quote from it:

Rose Siggins is why we’re here — an infinitely strong woman who isn’t strong enough this time. She, Luke, and Shelby need our help through this tough time. Rose is currently in the hospital and the outlook on her current health is grim. All funds raised will be used for the care of her children Luke and Shelby now. Once a path for care is set it will then be used for recovery, medical, and any other related expenses.

Is that first sentence not unspeakably crass?

The two kids, Luke and Shelby, are adults now, but they were children at the time. And it occurred to me that whoever had custody of them—the father was out of the picture—would have no way of tracking whatever funds appeared in Pittsburgh, and thus no way of knowing what the kids would be entitled to.

So I tracked down the woman who had custody of the children, in Pueblo, Colorado, and reached out to her on Facebook and let her know my concerns. She, of course, said that Bendig and his partner had been nothing but kind to them, and how dare I cast these aspersions. I told her that wasn’t the point. They may be very nice people, but the point is someone else has to have their eyes on the money. She didn’t want to believe me, and not feeling that there was any aggrieved party, I left it alone.

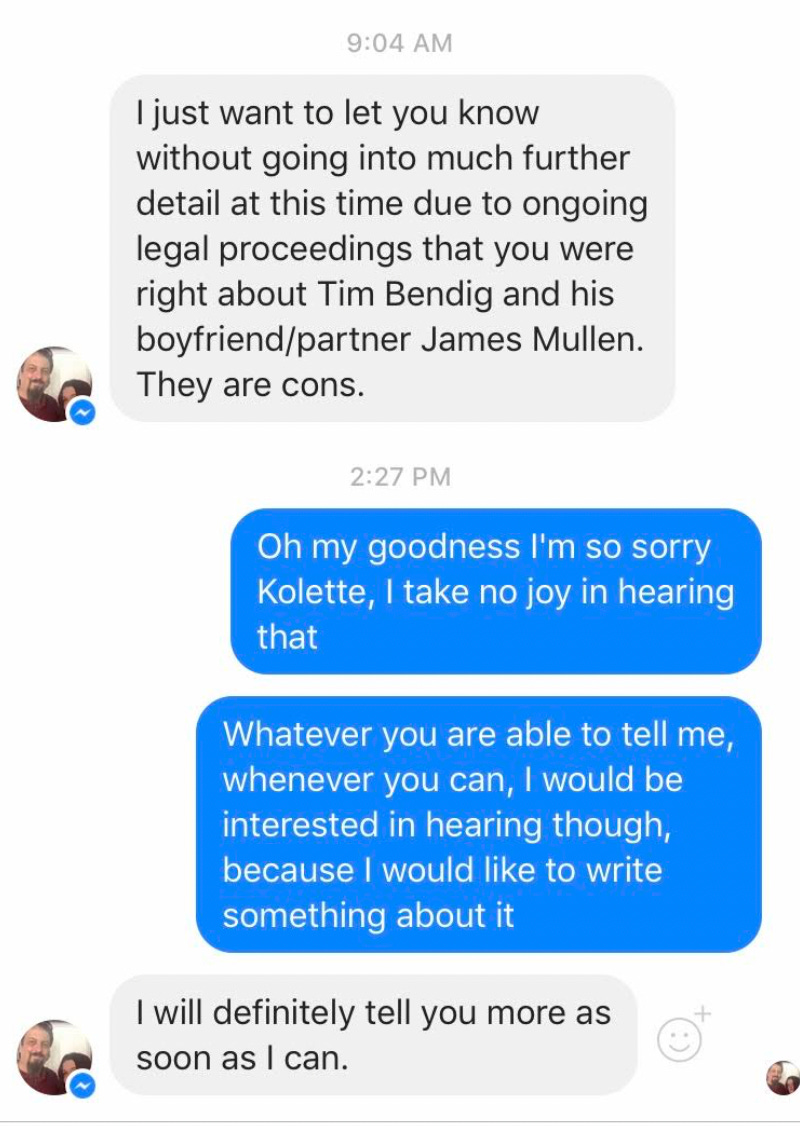

But about a year later, lo and behold, she reached back out to me and said I was right. I had left for Kansas by then, and Wuerl’s resignation came not too long after.

So, it looks like Cardinal Wuerl’s chief defender in the press on the abuse stuff was accused of bilking the orphans of a paraplegic actress. That’s pretty troubling.

It’s also interesting because Wuerl’s first impression of Bendig when it came to the abuse allegation was that it was all about money.

Clearly Wuerl changed his mind. And then the relationship persists for decades. Even very soon before his resignation, Wuerl felt compelled to defend the man from nameless bloggers on the Internet. This strikes me as, at minimum, some pretty cynical PR. And according to George Neumayr, who bulldogged these people for a long time, the Pittsburgh chancery gets very skittish about the Bendig deposition. It does seem to be true that there was really bad stuff going on in the Pittsburgh diocese at the time, but Bendig has serious credibility issues.

A source told me back in about 2016 that Bendig and his partner were under investigation by ordinary law enforcement, and that their bank records had been subpoenaed.

So much of this is divorced from any legally-established facts, that's one of the problems here. But I had the impression at the time, which has certainly been vindicated by subsequent events, that virtually nothing about Wuerl’s reputation on this stuff was true. I also find myself thinking, years later, that justice on this stuff probably requires defending good priests from false accusations as much as it depends on removing bad ones for true allegations. I don’t necessarily think Wuerl’s approach, of letting more of this stuff be handled in government courtrooms, is a bad one, but it’s also one he didn’t follow here, that’s why it’s interesting. I’m also very suspicious of the Pittsburgh press’s handling of this one. Maybe I should have written about this sooner, but I did what I could to get the kids the money they’re entitled to.