Pilgrim Diary: 27 Days on the Via di Francesco, from Florence to Rome

The joys of walking 320 miles during one of the rainiest summers in recent Italian memory

It’s hard to write about St. Francis because he means so many things to so many people. Nobody would dispute that he’s one of the greatest saints of the Latin church. He was canonized two years after his death—nobody seems to have doubted his sanctity, at least after his movement had started to get going. But he’s a complicated figure. Even if you put aside entirely the supernatural stuff—the miracles, the stigmata, and so on, his psychology is very interesting.

There are all of these moments of renunciation in St. Francis—from beginning to end, his life is full of them. When he strips off his garments in front of the bishop and renounces his inheritance, to when he leaves his order behind and goes to La Verna to pray, after the Franciscan Rule was approved. The former came, of course, after his own father had him locked up. This year is marks eight centuries from the latter.

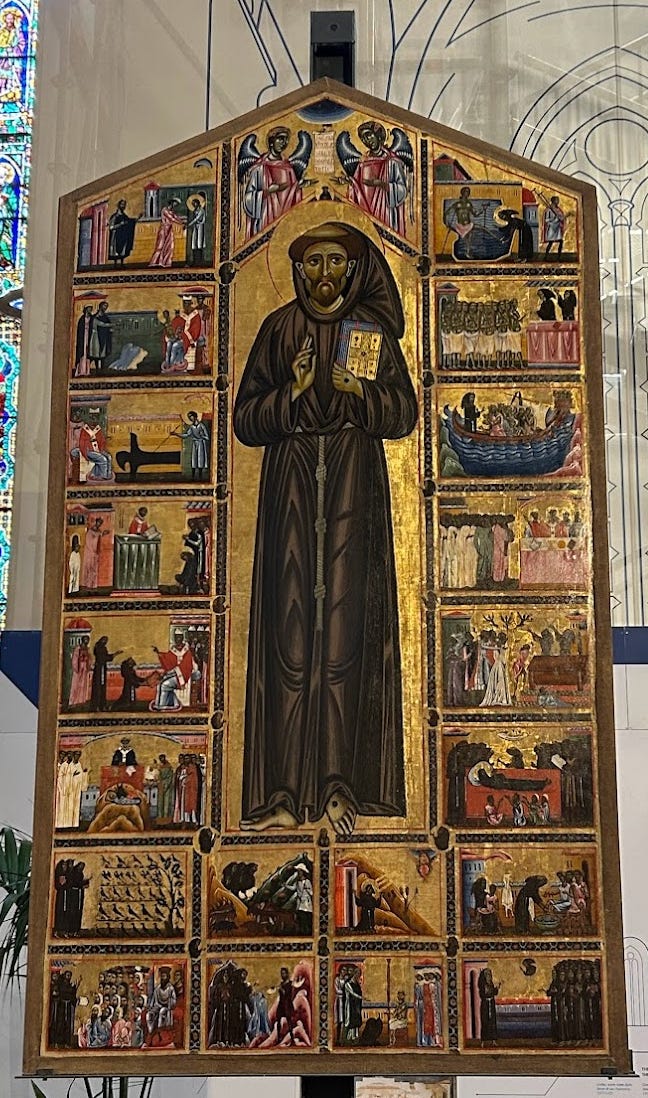

One thing I notice about St. Francis is how most writing about him has a cheerful quality, in line with the bright spirit of his own writing and the way he talked, but paintings of him can be rather dark. His own life was filled with these sorts of contrasts. He walked all over the place, but at other times he inhabited very small and very dark cells, some of which you can see on this walk.

The central contrast of St. Francis is how, during his own lifetime, he was seen as a spiritual leader. But that was in tension with his famous humility and desire to be the least of the brothers. The Augustine Thompson, O.P. biography published several years ago dwells at length upon this, and how Francis bore the burden of leadership. He did have an extraordinary understanding of human nature, which you can see in a lot of the moments of his life. Thompson struggles with Francis’s psychology, and finds himself wondering whether he was mad, something his own countrymen of Assisi surely wondered themselves. The line, I suppose, between madness and great faith is pretty thin.

I read Thompson’s biography before I left, but I read the Chesterton one on the trail, which is very short and lyrical, the first one he wrote after his conversion. All writers on St. Francis are at pains to clarify misconceptions about him, because there is a tendency to turn him into a sort of pantheist, environmentalist or a hippie. For all his love of animals, he was not a vegetarian; for his earthiness, there are anecdotes about him fussing over altar linens; for all that he represents a kind of holy vagabondage, he always returned home to Assisi. Most of all, there’s an incredible literalism and audacity to St. Francis—when God speaks to him in San Damiano to tell him to repair the church, he goes about gathering stones, which is like something out of Amelia Bedelia. When he’s tempted he throws himself into a thornbush. It’s OK to be amused by this, it is funny. And yet, his manner of address, even to animals and inanimate things, is courtly and polite—the bright circle in the sky isn’t a representation of a distant and powerful pagan god, it’s “Mr. Sun,” like the Raffi song.

He had this manner even in the darker moments of his life, it was something very deep in him. When his eyes were cauterized with a hot iron, he says “Brother Fire, be gentle with me,” and by one account, his last words were to welcome Sister Bodily Death. In St Francis you find the Provençal tradition of courtly love and chivalry baptized and put into the service of God, in much the same way that the late Pope Benedict XVI’s writing represents German romanticism having become fully Christian. You can read the Bible in almost any way, as a comedy, a tragedy, or any other thing. But in St. Francis you really get the sense of the Bible as a love story, a romance between God and man.

It is also true that St. Francis changed the world, started the great spiritual revolution of the Middle Ages, and his orders produce a disproportionate number of saints. Chesterton talks about the contrast between Francis and St. Benedict:

What St. Benedict had stored St. Francis scattered; but in the world of spiritual things what had been stored into the barns like grain was scattered over the world as seed. The servants of God who had been a besieged garrison became a marching army; the ways of the world were filled as with thunder with the trampling of their feet and far ahead of that ever swelling host went a man singing; as simply he had sung that morning in the winter woods, where he walked alone.

The military metaphor is somewhat out of step with the spirit of the thing—one of my favorite anecdotes from the Thompson book is how several friars greeted the army of Otto IV, marching through Italy in all its pomp and grandeur, by running out and shouting “All glory is fleeting!” But it’s a true enough sentiment.

I hesitate to use the word revolution, but the Franciscan movement probably did feel that way to a great many people. But it’s also true that the Franciscan story is also a story of the Catholic Church’s sense of balance and moderation. There is, undeniably, a sort of anarchic spirit in Franciscan spirituality, an insistence that the economy of grace works differently than the human world of balance sheets and ledgers. But it needed to be regulated, which is not just a matter of subtraction but in some cases addition—for instance, the Pope said the new order must preach, something Francis was reluctant to do.

With all that introduction, let’s talk about the Via di Francesco. It’s hard to get to know a person without understanding the landscapes they inhabit, and it’s been quoted in several places (I can’t find an attribution) that “the character of the whole Roman Catholic Church is visibly Umbrian” because of Francis. When you read American writers who were outdoorsmen, like Jack London or Hemingway, there is a certain hardness that resembles the American landscape. The Umbrian countryside is much more gentle, the kind of place that would produce a sense of the brotherhood of all created things.

The via di Francesco is 320 miles long, beginning in Tuscany and ending in Rome. As most of the guidebooks will tell you, it is more physically demanding than the Camino de Santiago in Spain, because there are more mountains. Most of the Franciscan sanctuaries are up on the sides of mountains, so to visit them you have to climb them. There are three types of landscape you’ll encounter, corresponding roughly to the three Italian provinces you cross through, and they get more smooth over time: the mountains in the Casentino Forest in the Tuscan Apennines, to the hills of Umbria, to the plains of Lazio. What that means is the first part is the most physically difficult. So training for the via di Francesco is probably a little more important than in Spain.

I probably met about three dozen other pilgrims doing long walking over 27 days, which means this route is, by a large margin, less well-trafficked than the Spanish Way. I think I counted five other Americans, a considerable number of Germans, mostly from the south, and a few Australians. It might have been because of all the rain they’ve been having this Summer, that people aren’t doing it, but it does seem to be the case that accommodations are a little more spotty than in Spain. It’s a little harder to reach hosts, things are more frequently closed, and you have to improvise a little more. You won’t, or at least I didn’t, find quite the same level of pilgrim camaraderie as you will get in Spain. On the other hand, that makes you very happy to meet the pilgrims you do see, and you feel a little more like you’re doing something special (even though pilgrims have been traveling to Rome for hundreds of years). Another big difference is that, because of the mountains, you want to plan your days more carefully. It’s best to climb in the morning and descend in the afternoon. If it’s getting to around noon, and you’re starting a second or even third substantial climb, you’re going to have a hard day.

Many, at this point I would say almost all, of the other pilgrims on both the Camino in Spain, and on the via di Francesco, are not Catholic. Even so, I find it a little puzzling that there isn’t an explicitly Catholic guidebook for any of these routes. The famous Brierley book for the Camino Frances is an excellent guide, but there’s an awful lot of new age hokum in it that I find a little tiresome. Your mileage may vary. There's a common German one written by a comedian, which sounds dreadful.

On this route there are a couple guidebooks, there’s the one by the Methodist Rev. Sandy Brown that several other English-speakers had with them. I took the one that came out this year, by Matthew Harms. On a day-to-day basis I didn’t end up consulting it much, and my own stages diverged some from the ones in there—mostly because I endeavored to go faster in the beginning to store up a few rest days I could spend in the interesting towns. But it’s necessary to have an up-to-date guidebook on this route. You need to have a couple of numbers to call for a bed in each town. In Italy, I found Apple Maps pretty unreliable out in the country. I used AllTrails much more frequently, many times each day, which maps the whole trail with elevations, and allows you to see very easily when you might have gone off track, or where you have taken a wrong turn.

If there had been more pilgrims on the route, I probably would have tried to stay in more of the parochial hostels for the camaraderie, but as it was I only saw maybe three dozen over almost four weeks of walking. With inns and bed-and-breakfasts being pretty cheap out in the country, I just stayed in those. I stayed in a couple of accommodations run by nuns, but they’re quite different than the parochial hostels common in Spain. I obviously ate and slept much better than Francis did when he walked over these hills—asking to be laid on the bare ground before he died makes him, to mind mind, sort of a patron of rough sleeping. I had a couple of 20+ mile days, but had a warm bed and a big meal at the end of it. If you want to know what it’s like to walk that far, then camp and sort out your own dinner, ask an AT thru-hiker.

No two pilgrimages are the same, but I’ll write a little about how I chose to do these things, this time. I happen to be a religious person, but even if you’re not the churches are the most interesting things to see on most of these pilgrim routes. You should visit them. My habit was to arrive in the town, visit the Church, thank God for getting me there, then proceed to where I was staying.

Before we get to the specifics of this journey, I want to describe four rules for pilgrims I try to observe.

Accept generosity. It’s spiritually meritorious to help a pilgrim, every religion teaches this. If people want to do something good for you, let them. Show gratitude, then pray for them at your destination. Even the people who served you a good meal or were nice to you, pray for them too. You probably needed the help anyway.

You can’t see everything. I missed a few things I wanted to see, and that’s OK. I wanted to climb to the Rocca in Spoleto, but it was raining and I wasn’t up to it. I wasn’t up to walking all the way to Greccio on an off day, so I missed what is referred to as the Franciscan Bethlehem. That’s OK.

Pain is part of the process. If you wait to walk until you don’t have any more dull pain in your feet, you won’t ever get anywhere—it’s more or less a constant. Offer it to God, have wine with dinner, and keep going. Sharp pain, blisters, or pulled tendons can be different (though most blisters can be treated and walked on).

No matter how far you’re going each day, try to be halfway done by 10 AM. This is important, as everyone who’s done the Spanish way knows. If you’re still walking at 2 or 3 in the afternoon when the sun is high, you won't have as much time to rest, you’ll be tired, and it will be unpleasant. If you’re walking 20 miles some day, start at 5 AM. It’s a little more difficult to keep this one in Italy, because Italians don’t even think about eating dinner before 7 or 7:30.

Some people like to take something to eat with them in their packs. I didn’t do this at all, and many days I skipped lunch. There are spots in many stages to stop for a coffee, or buy some fruit. I would have a small breakfast and a large dinner. After having only eaten a pastry or two, and then walking all day, I was ready for a full three-to-four course Italian dinner, which under normal circumstances is a whole lot of food. A lot of people come to Italy to eat, and the food is some of the best in the world. You’ll never appreciate it more than if you’ve walked 15-18 miles without lunch.

T -1, O: Florence

I had two full days in Florence before getting on the trail. My credential was not, in fact waiting for me at the hotel as I expected, so I fully planned to get walking without one. I spent the two days seeing the sights and preparing. I arrived on Sunday and went to Mass at the Duomo, then saw the Uffizi and Accademia, and a couple of the smaller churches in the afternoon, including the Chiesa di Dante. The second day, I walked out to the northern side of the city, to see the Basilica of the Annunciation, the archaeology museum that holds the Medici collection of cameos, and the English cemetery. If you’re into cemeteries, that’s a very cool one, where you’ll find many of the Brits and Americans who died in Florence: it inspired Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead painting, and in it you’ll find the graves of the American sculptor Hiram Powers (famous for The Greek Slave), Arthur Hugh Clough (a companion of Florence Nightingale who wrote the poem “Say Not the Struggle Naught Availeth”), and the abolitionist preacher Theodore Parker. On the way to the Santa Croce I visited the Grand Synagogue. For dinner, I allowed a waiter on the Piazza Vecchio to hustle me into buying an expensive steak Florentine, which was very good.

Day 1: Florence to Diacceto, about 16 miles

I got a late start. After scarfing down a quick breakfast at the hotel, I decided to try for a credential at the Anglican church in Florence, which is on the Western side of the city, which meant adding about two miles to the day. Fortunately, they did have one. Walking East, the workers at the Santa Croce did me a solid by giving me a stamp even though it was closed, so my credential had a Florentine stamp at the beginning. I reached the outskirts of the city in the rain around 8:30. It’s about 12 miles to Pontassieve, mostly along footpaths that follow the Arno. I reached Pontassieve around 1 PM, and had a coffee and a sandwich. From Pontassieve you begin to climb. I was very tired when I reached the BnB in Diacceto, but roughly half the climb of the next day was done. The BnB was run by a lovely couple named Francesco and Andrea and their two dogs, and decorated with a lot of African art. I was the only pilgrim, and they served a delicious dinner of pasta and a pork chop with vegetables.

Day 2: Diacceto to Stia, about 18 miles

It was raining when I left that morning around 7. The temperature was about 45 degrees, but because my sneakers got soaked the previous day, I decided to wear sandals anyway. That was good, because it’s better to wear sandals for stream crossings, but it was very cold. Over the next eight miles uphill to Consuma, on trails, everything on my person got soaked. The trails were in awful shape, and I was slipping a lot. So it was slow going. I got to Consuma around 11:30, shivering and I’m sure looking like a wet dog. I was shivering in the doorway of the local church when a German family poured out of a taxi, and were nice enough to let me into the hostel next door, and I chatted a bit with their daughter who spoke very good English. The lady who ran the hostel, who turned out to be the cousin of the woman I was staying with in the next town, started a fire and made me some tea and cookies, and I sat there dreading the next ten miles for about two hours.

The rain did let up a bit and I started walking again around 1:30, but taking the roads instead of the trails, because that morning had been right on the verge between difficult and genuinely dangerous. In the cold weather you really learn to appreciate a bit of sunlight when it comes, and I got maybe 45 minutes of sunlight on my skin on the walk down, which felt very good.

About five miles out, a nurse named Lisa, who had spent the day in Florence visiting a friend, offered me a ride. She wanted me to see an old Romanesque church about two miles outside the town, Pieve San Pietro di Romena, so she let me off there. I told her I would be fine walking the rest of the way, then went to see it.

I arrived in Stia, a town near the headwaters of the Arno, around 4 o’clock. I had left my vape at the BnB. For a few hours that morning, I briefly considered treating it as an instance of God stripping me of my vanities, and going without for the rest of the trip. The rest of the day persuaded me to buy an Elfbar as soon as I could. I stopped at two of the local churches to pray on the way to my accommodation, one of which had a couple of della Robbia sculptures. My host had been looking for me when I got there. Her name was Olga, and I later found out she is quite famous among pilgrims for being a wonderful host. She certainly was to me. I arrived in her beautiful apartment on the main square, and I told her my clothes were all wet. She took them, and they were waiting for me, dry, the next morning, which really saved my hide. She made me green tea, and we were sitting in her kitchen trying to communicate as best we could, until she told me to go lie down, which I was very happy to do. Her guest bedroom was beautiful, with a bunch of icons and an antique bed. I lied down until dinnertime. For dinner she sent me to the Ristorante di Falterona down the street. I had some cold cuts, pasta with shrimp, a fancy porchetta and some ice cream, then went to sleep with a lot of pain in my feet.

Day 3: Stia to Badia Prataglia, about 16 miles

I left Stia around 7, preparing for a difficult climb into the Casentino National Forest. The sun was really shining for the first time of the trip, and I saw some animals that morning. Lots of deer tracks, and a couple of jays. There was a lot of climbing during this stage, and it was difficult, but the scenery is just beautiful.

I arrived in Camaldoli around 12:45, where many other pilgrims stop for the day. I caught the monks at their midday prayers, and listened to them until they finished. The Camaldoli monastery is where the Camaldolese order began, in the 11th century, by St. Romuald. There was an even more famous hermitage several kilometers north, which I didn’t have time to visit.

I wanted to eat before finishing the last 8 or so kilometers to Badia Prataglia, so I went to a deli specializing in cinghiale, or wild boar. They had it prepared in just about every way you can imagine, cinghiale salami, cinghiale mortadella, and so on, but I had some grilled sausage on a sandwich, and I asked for extra cheese, and ate it with a bowl of chickpea soup. It was a memorable sandwich, the kind of sandwich you don’t forget.

I left Camaldoli around 2, thinking the rest of the day would be simple, but it was not, and it took me around three hours. The stream crossings were all swollen. The climb to the top of Poggio Brogli was the most difficult of the trip so far. I arrived in town, and the innkeeper was smoking in the lobby. So I thought, this is my kind of place. He loaned me an electricity converter, and I charged my phone, visited the church, had a beer at the bar (this being the first town in several days with a proper one), then returned to the hotel for dinner. There was a pair of Swiss guys who were sticking to the roads, who were staying in the same hotel in La Verna the next day, and a big group of Germans. La Verna was only about 10 miles away, but the forecast was between 45 and 55 degrees and rainy, so it was going to be a difficult next day. None of the radiators are turned on, even though it’s cold, so I put an extra blanket on my bed.

The news was full of stories about the horrible conditions right over the mountains in Emilia-Romagna—they cancelled the F-1 race in Imola, a few people drowned in Ravenna. It occurred to me how crazy it is to be walking in all this, but the hardest part was almost over.

Day 4: Badia Prataglia to La Verna, about 10 miles

For the final stretch into La Verna, you make three ascents (depending on which route you take, there are mountain trails that spiderweb this whole area). First Poggio della Cesta, then Poggio Montopoli, and then the climb to the mountain where the La Verna sanctuary is. Descents were hard and slippery. I walked for part of the day with a Bavarian fellow who was doing some of the route with his family. His elderly father was taking the roads, but he was up on the trails. He loaned me one of his hiking poles for the descents, which was nice because airport security had taken mine, and I had none.

The landscape changes a little bit on the trail into La Verna, you start to see a lot of big rocks covered in moss, that look like this:

I arrived at the foot of the mountain where La Verna sits, and considered just walking downhill to the town and walking up to the sanctuary in the morning during my rest day. But I went for it, and am glad I did. I arrived at the sanctuary around 2:30, through the gate in front of the Chapel of St. Mary and the Angels. So that’s the first place I stopped. It’s a very special place, and the wet and foggy conditions kind of heightened the drama of it. The best way I can describe it is like a Miyazaki film—in a lot of American movies, mystery is something threatening, or to be feared, but not in Miyazaki, and not at La Verna.

The La Verna complex is a whole set of chapels and sacred places fit to the mountain, it’s really a special place, I’ve never been anywhere that felt quite like it. St. Francis was given the mountain by a nobleman, and it’s where, two years before his death, he received the stigmata. There’s a chapel that sits over the spot where it happened, and every day the Franciscans who live there process to it from the main sanctuary, down a hallway with a series of frescoes depicting events in his life. I arrived at 2:30 and walked around for about a half hour before the monks began. They sing Crucis Christae mons Alvernae, a hymn about the stigmata, on the way there, and then a litany on the way back. The former was translated in the 19th century by Edward Caswell, here’s the first verse:

Let Alverna's holy mountain

That high mystery proclaim,

Of the stamps of life eternal

Which on blessed Francis came;

While he sobb'd, and while he sigh'd,

Grieving for the Crucified.

People today aren’t inclined to believe things like this can happen. Even if you’re that sort of person, the thing to keep in mind is that the story of St. Francis kind of doesn’t make sense without it. It may not make sense according to the laws of nature, but according to the laws of narrative, it does.

St. Francis was a man of extraordinary humility, and it’s supernatural grace that arrives to lift him up. In one of the other moments of his life, he goes up a mountain to pray and do penance, and an angel appears to him and reassures him that his sins are truly forgiven, presumably because he had doubts whether he could have deserved such a thing. He comes down the mountain proclaiming that God is forgiveness and mercy. In a similar way, toward the end of his life, when he’s up on another mountain, God finds this humble man worthy to bear the very wounds of Christ. To bear them is to suffer—by all accounts they were very painful for him. Afterward he wore socks. Without the stigmata, we might be left with an affable eccentric poor man singing his way through the hills of Umbria, but along with that is a man who went to the top of the mountain to suffer. The story doesn’t make sense without it.

La Verna is a very moving place. Before leaving that evening I visited his cell—really a crevice between two rocks, with another rock as his bed. In the sanctuary is his robe, and some other relics.

I walked down the mountain around 5 to where I was staying, and ate dinner. The innkeeper brought out a bottle of Veleno Borgia for me afterward.

Day 5: Rest Day at La Verna

At this point I had done in four days what the guidebook says to do in six, so I had stored up two rest days, one of which I spent here. I slept in until 8, and loafed around until noon, before walking up the mountain on the road to spend the afternoon at the sanctuary, having some ravioli at a little restaurant just outside. There were some nice motorcyclists there, who looked at me a little skeptically when I told them I had been in the mountains for the last couple of days. This time I walked in through the front door.

I looked at some of the art, filled up my water bottle from the fountain at the foot of the cross, and spent the better part of two hours sitting in the beech forest a little up the mountain from the sanctuary. It’s a very beautiful place. The colors of it, the ground is reddish, the sky was gray, the trunks of the beech trees are bright, and everything else is green. Another Franciscan beatus is buried up there, so I asked for his prayers and looked around a little. Then I prayed with the monks again that afternoon. There’s a little plaque on the way down from the Bosco Sacro, which reads:

Mount of secrets most holy and divine

St. Francis here with the wounds of Jesus marked

united his life with the sufferings of our Lord,

streams of life now flow into all the world.

It was Sunday, so I waited in the stigmata chapel for Mass with a group of Italian students visiting the sanctuary, then went back down.

That night I had a few drinks with a biker, who rather ambitiously told me he was going to ride all the way to Turin, which doesn’t seem like the kind of thing a person can do, but who knows.

Day 6: La Verna to Pieve Santo Stefano, about 10 miles

From here you walk out of the Casentino Forest, but there are still two days of walking before leaving Tuscany. Over the last few days you’re crossing from the Arno watershed into the Tiber watershed, and you catch the first view of the Tiber in Pieve Santo Stefano, where it’s not much more than a clear, beautiful creek. I woke up at 5 and read until 7 because it was a short day. There were some lovely mountain meadows along the way. For many of the following stages, you’ll climb in the morning, then follow a ridgeline during the day, which is how many of the Etruscans would walk these routes—following the ridges. I passed through Monte Castel Savino today, which is along one.

I arrived in Pieve Santo Stefano around 1 and ate a two slices of pizza. There was some sort of motorbike race going on, with a lot of tents put up and people wearing pads walking around.

I visited the local church, then headed to my hotel, which was about 1 km south of town on a freeway exit, what we would call in the U.S. a roadside motel. I went there to relax for a long stage the following day.

Day 7: Pieve Santo Stefano to Sansepulcro, about 22 miles

This being one of the longest stages of the route, and with a significant distance back into town before even starting, I got an early start. I woke up at 4. No hotel staff were there, but I checked with the people who ran the cafe attached to make sure my bill was paid, and got on the road by 4:30, so I was walking in the dark for several hours with a headlamp before the sun came up.

There’s a considerable ascent for about seven miles in the morning to climb the Alpe della Luna, the alp of the moon. It’s a very difficult stage, one of the hardest of the trip, but the walking is incredibly beautiful.

I stopped for a second caffe doppio at 7:30 in the morning with about .8 miles to go to the summit. The final ascent thereafter is very difficult. With the top in view, there was a herd of white cows standing between me and it. I got close, and they ran away from me, further up the hill, making a terrible racket with their cowbells. They were still on the trail, so I got closer again, and they ran away again, further up, with the hill getting steeper. I was astonished that these cows could navigate the steep slope. I lost track of them very near the top, they disappeared while I was huffing and puffing.

For the rest of the day you’re along the ridge line or descending, and you get to enjoy the views, which are magnificent.

At about the halfway point, which I did manage to reach by 10 AM, I stopped for a third coffee and some water at a very remote mountain lodge within the Alpe della Luna park. You pass through the hometown of the beatus Fra Raniero of Sansepolcro, a 16th century Capuchin mystic who lived at Montecasale, the monastery at the end of the day’s walk. On the way there, the landscape thins out a bit and you get a lot more exposed rock that reminds me of hiking trails in the U.S.

At 12:30, and with about seven miles to go, I stopped in the little hamlet of La Montagna to fill my water bottle. I was chafing pretty badly by that point, and I switched to my sneakers.

The place of Montecasale in the Franciscan story is that it is where three thieves were converted, and St. Francis cast out a demon. One of his followers, Brother Angelo who Francis had made the guardian of Montecasale, was distributing food, and refused to give any to the thieves, knowing of their reputation. St. Francis rebuked him, and told him you make converts with kindness. Francis sent him back with bread and wine to give to the thieves, who, moved by the kindness, joined the Franciscan order. It’s a very beautiful story, here’s one version of Francis’s rebuke of Brother Angelo:

They would be brought back to God more easily by sweetness than by cruel rebukes. Therefore our teacher Jesus Christ whose Gospel we have promised to observe, says that it is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick, and that He did not come to call the just but to call sinners to repentance, and for that reason He often ate with them. Therefore, since you have acted against charity and against the holy Gospel of Christ, I command you under holy obedience: immediately take this sack of bread and jug of wine that I obtained and go after them diligently through mountains and valleys until you find them. Then on my behalf present all this bread and wine to them. Then kneel down before them and humbly tell them your fault of being cruel. Then ask them on my behalf not to do evil anymore, but to fear God and not to offend their neighbors.

I arrived at Montecasale around 2:30, went into the chapel to pray, and sat by the statue of St. Francis for a little while.

Here’s what it looks like, it really clings to the side of the mountain.

I had passed two Italian ladies walking the stretch from La Verna to Assisi, and they told me as I was leaving that some people in Montecasale told them to take the road for the descent to Sansepolcro rather than chancing it with the trail. Having been on some difficult descents, and looking at the near-vertical line on AllTrails, I followed that advice. It added about two miles, so between that and the extra kilometer at the beginning of the day made today’s walk about 24 or 25 miles. Which is a very long day.

Along the road there are stations of the cross, which I was seeing in reverse because I was descending. Every muscle in my legs was screaming at me at this point, and I must have had a little too much desperation in my wave at a passing motorist, because he slowed down and asked, “tutto bene?” I should have told him, no, I am absolutely not tutto bene. I am the furthest thing from tutto bene. But my pride got the better of me, and I told him, yes, I was fine, and kept walking. I arrived in Sansepolcro around 5.

I was deeply exhausted but decided I was going to see the Piero Della Francesca Resurrection even if it killed me. Aldous Huxley called it the greatest painting ever made. The civic museum was closing five minutes after I got there, so I had to see it through glass. But I saw it.

I’m very sure I looked like an absolute fool, shambling around the town square in pajama shorts, a t-shirt and fanny pack, peering into windows and walking into every church I pass by. But I visited the cathedral—there’s a nice painting of St. Thomas—and had a conversation with another Italian pilgrim who shared my name, Giordano, who was making some sketches. We talked for a little while. I chatted in the square with a British couple who lived in the area enjoying their retirement—they had a nice truffle dog with them and bought me a beer—then had dinner with a government attorney from Bavaria who was also walking the trail. The Italians were impressed that I had walked all that way, one of them said I had done two days in one. Then I lanced three blisters and went to sleep.

Day 8: Sansepolcro to Città di Castello, about 12 miles

The guidebook has the distance here done in two days, going back up into the hills and stopping for the night at a picturesque little town, but I was very tired from the day before and wanted to save another day, so I walked along the Tiber. I woke up at 8, because it was a short day. It’s a very pretty walk, and there was all this fluff coming off the trees.

At some point along this trail, you cross over from Tuscany into Umbria. I arrived in Città di Castello around 1:30, with plenty of time to enjoy the town. My watch had broken the night before, and I had to visit a jeweler to press the back on. One of the best things about these mid-size towns are the local pinacotecas, which are a great way to pass an afternoon. The one in this city is quite substantial, they have a few Rafaels and Signorellis, di Chirico’s Italian Piazza, and a few big gonfalon that are very cool.

The patrons of these towns are often obscure, ancient saints I’ve never heard of—the cathedral here is dedicated to Sts. Florido and Amanzio. It’s interesting to read their stories. Outside the cathedral, I bid farewell to the Bavarian I walked with outside of La Verna, and his father. They were headed back home, he told me his children missed him and his wife wanted him back. I had dinner again with the Bavarian attorney, at Trattoria Lea, a great restaurant on the main square. They had some of the best prosciutto I had on the whole trip, and I had pasta alla tartufo and grilled lamb, with tiramisu for dessert.

Day 9: Città di Castello to Pietralunga, about 18 miles

During this leg you start to appreciate the difference in landscape between Tuscany and Umbria. There are still climbs, but they’re noticeably gentler, and you can walk further. I started out from the town at six, had coffee just outside the town, and then another one on the way up into the hills.

I arrived at Pieve di Saddi a little after 11, an old church attached today to a parochial hostel. The couple who run the hostel were pulling up right as I arrived, and they let me into the church. This is, according to some literature, the site of the martyrdom of St. Crescentian and the martyrs of Saddi. I was in the church by myself, and the lady who runs the place pointed for me to check out the crypt.

I spent about half an hour there, refilling my water bottle, lighting a candle and enjoying the sunshine, then proceeded on to Pietralunga, and I arrived around 2:15. A really nice day of walking, though mostly on roads. A lot of pain in my feet, but the chafing was not so bad.

Pietralunga, like many of these towns, sits on a hillside, and the town is very vertical. A man stuck his head out a car window and welcomed me to the town. I chatted briefly with two women from northern Germany who I would see in several towns over the following days. I visited the church in the evening after dinner and some people were praying a rosary. The church and the Lombard tower look lovely at night.

Day 10: Pietralunga to Gubbio, about 17 miles

Woke up at 5:30 and had breakfast at 6:30 when the people who run the hostel arrived. Another really lovely day of walking.

In the two days from Città di Castello to Gubbio, you cross from the Tiber valley to the valley where Gubbio is, and in the second half of this day you enter the latter, with beautiful views of the whole thing. Before reaching it you travel through some nice forests, where I saw some deer, and I think I saw a wolf, but can’t be sure because there was also a man letting out his hunting dogs. These few days are associated with the route St. Francis traveled after he stripped himself and renounced his inheritance.

I stopped in a churchyard on the edge of the valley to fill my water bottle and stamp my credential, and as I was resting a lazy dog came by to say hello.

From there you go down into the valley floor for a while, before walking into Gubbio. As many tourism guides will tell you, Gubbio is a very unique place. It feels like a Game of Thrones set. It’s full of medieval buildings. I had considered staying at an old monastery outside of town that had been turned into a nice hotel, but I’m very glad I decided to stay in the center of town for the extra rest day I would be spending there.

I checked into the Hotel Bosone at about 1:30, showered and laid down for a couple of hours. I had a great room with a rooftop patio, which I used to dry clothes.

In Gubbio you really get a sense of what Italians call campanilismo, or pride in one’s place. The city is famous for an event called the Corsa de Ceri—you’d call it in English something like “the candle race”—which had just happened a few weeks earlier. Its origins are in the rivalries between city guilds, with three separate saints for patrons, who race images of them up to the basilica at the top of the mountain, where the relics of St. Ubaldo, the city’s patron, are found. Each of the teams have a different color, and all over the city, banners for one or the other are hanging out of windows, which also helps to give the city a very medieval feel.

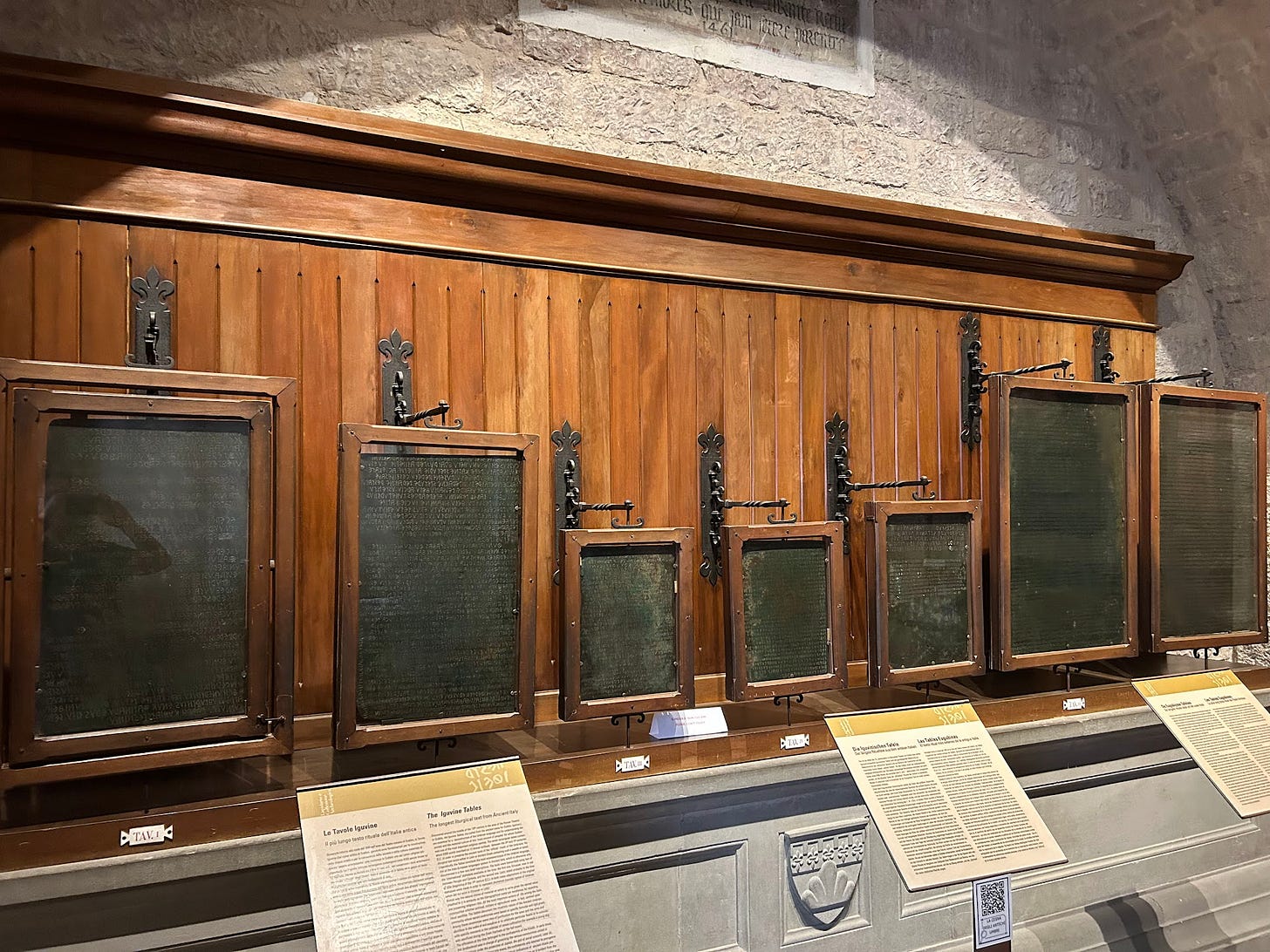

After sleeping for a few hours, I visited the palazzo on the main square. There are some paintings inside, and an archaeology section on the ancient Umbrians, as well as a small collection of items from Tibet courtesy British army officer Vivian Gabriel, but the most interesting artifacts there are the Iguvine tablets. They’re a series of seven bronzes on which are written the oldest record of the religious rites of the ancient Umbrians—mostly what animals to sacrifice, how, and for what reason.

Like a lot of these small civic museums, most of the best art is local: Here there are works by Benedetto and Virgilio Nucci and Felice Damiani, who were all from Gubbio. You can go to the top of the tower and get great views of the city and the valley below, I sat up there for about 25 minutes.

After that I climbed further up the hill to visit the ducal palace and cathedral. The diocesan museum was small but nice, and the ducal palace was filled with a bunch of portraits of eminent Gubbians. I walked down to the garden beneath the ducal palace and had a coffee as afternoon set in. It’s a very nice place to rest your feet.

Back down on the piazza around 6, the balestrieri di Gubbio were practicing, right there in the middle.

Once a year, these gentlemen will go up against the balestrieri di Sansepolcro to see who has the better crossbowmen. I was impressed by how accurate they were, these guys were hitting the center of the target almost every time. You read about medieval battles where the crossbowmen can never hit anything and they’re always getting killed, but these guys were real crack shots. I walked down to the San Martino neighborhood for an apertivo, and on my way back caught some sort of medieval pageant, guys flipping flags and playing drums and trumpets.

I ate very well in Gubbio. I had a very Umbrian dinner that night at the Ristorante Federico da Montefeltro. There’s a local pasta variant called strangozzi, which is supposed to not have eggs in it. So it’s heavier and thicker than spaghetti, and it can stand up a heavy sauce, and here I had it with a goose ragu. A few Italians laughed at me when I told them it reminded me of udon. They’re very grillpilled in Umbria too, so for a secondo I had the mixed grill.

Day 11: Rest day in Gubbio

I woke up around 7 and ate breakfast in the beautiful hotel dining room, with a plan to see the churches I had missed the day before. It was sort of a slow day, which I was in need of after a few heavy days of walking. I visited the Parish of St. Augustine first, which has some wonderful frescoes, then waited around for the funivia to open to take me to the top of the mountain and the Basilica of St. Ubaldo. Riding the funivia is like riding in a birdcage.

The sanctuary at the top of the mountain is a very neat place. I’m not going to tell you I had ever heard of St. Ubaldo before I got there. But that’s where his body is, along with the three ceri for the annual race.

I had a coffee at the top of the mountain and descended by foot down the trail to the basilica, and then through the Ranghiasci Park. Later that afternoon I visited the the church of St. Francis, and the Chapel of the Peace, which is named for the story that famously connects the city with St. Francis, the wolf of Gubbio. I was disappointed to learn from Augustine Thompson that this story is probably a bit of pious folklore. You probably don’t want to tell the locals that. Anyway, the way it goes is, a wolf was eating the babies and livestock of the city, and they asked St. Francis to have a word with him. The wolf put his paw in St. Francis’s hand, and thereafter he was a good boy—Fratello Lupo, brother wolf. He begged for food from the townspeople, who were happy to keep him fed. This is sometimes called the peace of Gubbio, hence the name of the chapel. There’s an awful lot of art depicting St. Francis with the wolf.

In the evening I sat on the piazza making conversation with a Swiss architect. We talked about politics and Andrei Malreaux. Some of the locals bought me a cocktail, and there was a band playing in the street. I haven’t the faintest idea what everyone was celebrating, with the pageant the night before and the band today, but everyone seemed very happy.

I had dinner at the Taverna del Lupo, with three kinds of carpaccio and pasta with a white ragu, then went to bed because the following day was going to be very long. I really enjoyed the day and a half in Gubbio.

Day 12: Gubbio to Valfabbrica, 25.4 miles

The guy at the hotel let me have breakfast before it was supposed to open, so I could get some coffee and cold cuts in before starting to walk. From here, it’s two days to Assisi, and you cross the hills into the Spoleto valley. This day’s walk is hard, but the next day into Assisi is fairly easy. It’s about four miles across the valley before you start to climb, so I blasted “Gimme Shelter” to psych myself up. The valley on a cool morning is just lovely.

About 11 miles in, I reached the St. Peter’s hermitage and albergue, a lovely little spot to take a break and refill my water bottle. A pilgrim from Colorado, one of only five Americans I met on the road, was leaving right as I got there.

The last eight miles or so you walk mostly in view of a lake. It’s very nice, but the distance made this day somewhat painful. At 11 or so, about 2/3 of the way up the final climb for the day, I got a terrible cramp, so I laid down on a sunny rock underneath a fig tree, by some poppies, and drank water.

I took another break at 1:30. Tootally exhausted, I threw my pack down by the side of the road and lied down with my head resting on it. After about a half hour, I got up and finished the last four miles.

I arrived in Valfabbrica around 3:30. I chatted with a Danish pilgrim walking with an East German woman when I got into town, then when they left to find their beds, I talked to a nice Dutch couple taking a vacation. The lady chided me for vaping. I told her she was right and I really ought to have a cigarette, being from Virginia, where tobacco is our business. She told me that was a good excuse.

As a tobacco-related aside, Italy seems to be the country where people are actually using the iQOS, the Phillip Morris heated tobacco product. I tried it when they rolled it out and didn’t care for it, but clearly the Italians disagree. I saw tons of young people using it.

I had a nice dinner with the Dane, the German, the woman from Colorado and two Italian ladies.

Day 13: Valfabbrica to Assisi, about 9 miles

Walking long distances teaches you a lot about patience, especially toward the end of the day when your body is hurting. Your lizard brain can’t stop looking at the watch and the map, even though your rational mind knows pretty well when you’re likely to actually finish. On a short stage like this one, you look at a church on top of every hill and wonder if that’s Assisi. It takes some time before it actually is.

I left late that morning because it was a short day, but after doing 25 miles the previous day, I was still quite sore. The walking is very beautiful.

Most people who arrive in Assisi by car come from the West, so they see it in a grand way, sitting on the hillside. Like a lot of these hill towns, Assisi is very vertical, so you can see the whole thing approaching from that direction. Approaching from the North, as on this route, you see the rocca first, then the Basilica of St. Francis, but the rest of the town is hidden.

I arrived at the basilica at 11 AM, with things to do. The upper basilica was closed to visitors, so I went to the lower one. It was a Sunday, and Mass was starting, so I made a quick confession beforehand. I was given a penance that would end the day I was to arrive in Rome, which was very appropriate. After Mass, I spent a few moments a little overcome with emotion, then visited the tomb of St. Francis.

There were lots of other people filing into the crypt, touching the tomb and so on, but there were enough seats in the pews for me to take my pack off and sit for a little while in front of it. If I had known it had been so busy, I might have dropped my pack off at my accommodation, but the route ends at the basilica, so who has time for that? St. Francis is buried with some of his companions, so I asked for their prayers too.

Spiritual matters taken care of, I sought out the pilgrim office for my testimonium. I got the sense, both here and in Rome, that they aren’t quite as used to long walkers. The pilgrim office in Santiago is a very streamlined thing. Here, it was just me and a nice lady with a printer, who checked my stamps and then gave me the certificate. I asked for a tube, which they charge two Euro for, because I was only halfway done.

When you walk long distances you become very eager for conversation. A lot of Americans visit Assisi, and I ended up having a few drinks with some of them, but the first few I met didn’t want to talk. Far be it from me to disturb their spiritual journey, but I was disappointed.

For the rest of the day I visited the major churches in Assisi. The Chiesa Nova, where St. Francis was imprisoned, the Basilica of St. Clare, where the Cross of San Damiano hangs today, the Cathedral of San Rufino, with its crypt and museum, and Santa Maria Sopra Minerva, where in a bit of bibliomancy St. Francis and his first few companions received their charism of radical poverty.

There’s a description in the basilica of the meaning of the Tau cross, a symbol to which St. Francis was very devoted. It’s very nice, so I’ll transcribe the whole thing here:

The Hebrew people, like many other ancient cultures, progressively elaborated a theology, or a complementary spiritual interpretation proper to each letter of the alphabet.

Because the Hebrew Scriptures, and therefore the Hebrew alphabet, was not formally codified until almost two hundred years after the birth of Christ, many letters were sometimes shaped in a variety of forms depending on the regions where Jews were living, either in Israel or in the “diaspora,” somewhere outside of Israel, usually in the Greek-speaking world.

The last letter of the Hebrew alphabet represented the fulfillment of the entire revealed word of God. This letter was called the tau. It could be written as /\, x, +, T. When the prophet Ezekiel (9:4) uses the imagery of the last letter of the alphabet, he is commending Israel to remain faithful to God until the last; to be recognized as symbolically “sealed” with the mark of the tau on their foreheads as God’s chosen people until the end of their lives. Those who remained faithful were called the remnant of Israel.

Although the last letter of modern Hebrew is no longer cross-shaped as described in the variations above, the early Christian writers commenting on the Hebrew scriptures (the Old Testament) used its Greek translation (the Septuagint) in which the tau was transcribed as a T.

For Christians the T came to represent the cross of Christ and the fulfillment of the Old Testament promises. The cross, as prefigured in the last letter of the Hebrew alphabet, represented the means by which Christ reversed the disobedience of the old Adam and became our Savior as the “New Adam.”

During the Middle Ages, the religious community of Anthony the Hermit, of which St. Francis was familiar, was very involved in the care of lepers. These men used Christ’s cross shaped like the Greek T as an amulet for warding off the plague and other skin diseases. After his conversion, Francis worked with these religious in the Assisi area. He eventually accepted and adapted the T as his own crest and signature. For Francis, the T represented life-long fidelity to the crucified Christ; it was his pledge to serve the least, the leper and the outcast of his day.

The tau imagery was intensified when Pope Innocent III opened the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, using the same exhortation as the Old Testament Prophet Ezekiel, “We are called to reform our lives, to stand in the presence of God as righteous people. God will know us all by the sign of the tau marked on our foreheads.” This symbolic imagery, used by the same pope who commissioned Francis’ new community a brief five years earlier, was immediately taken to heart as the friars’ call to reform. With arms outstretched, Francis often told his brother friars that their religious habit was in the shape of the tau, meaning that they were to become “walking crucifixes,” models of a compassionate God and examples of faithfulness until their dying day.

Today, followers of Francis, as laity or religious, wear the tau cross as an exterior sign, a “seal” of their own commitment, a remembrance of the victory of Christ over evil through daily self-sacrificing love. The sign of contradiction has become the sign of hope.

Maybe we should call a pilgrim on the via di Francesco a T-mobile. (Sorry!)

In the evening I chatted with a group of pilgrims from North Dakota, who were traveling around Italy with their priest for two weeks.

Day 14: Rest day in Assisi

I woke up at 6:30, had a coffee in the piazza because breakfast wasn’t ready yet, and pet a cat that one of the locals told me was named Prince. Later that day someone put out food for him and he was chowing down. He was a nice boy, not afraid of anyone.

After breakfast I walked to San Damiano, arriving before it opened, and prayed in the chapel.

There was another American group there led by a Franciscan friar from Indiana. He told me that I had to visit the Eremo di Carceri above the city, the hermitage where Francis and some of his companions often prayed. First I continued down the hill to St. Mary of the Angels, to visit the Porziuncula and the spot where Francis died.

I found myself on the bottom of the plain around noon, but I had to go to the hermitage way above the city because of the Franciscan’s suggestion. I wasn’t too keen on climbing a mountain on my rest day, so I took my one cab of the trip. I’m very glad I did, because it’s beautiful up there. These mountain hermitages along the way are partly what makes the via di Francesco difficult—you have to climb to reach them—but they’re also very special places. Up high, but shady. The way they feel is very unique, it’s hard to describe. At the Eremo di Carceri is a hole in the floor where St. Francis cast a demon.

Also up there is the tomb of Barnaba Massei, who devised a credit scheme that was part of the Church’s many creative attempts to deal with the problem of usury. The Mons Pietatis is sometimes described as the first modern pawn shop.

My cab driver was nice enough to wait around for a while at the top of the mountain to drive me back down again so I could continue seeing the city. I visited the tomb of Carlo Acutis, then went back to lie down and think about the next two weeks of walking. I had been walking a bit faster than the guidebook so far, to save up some rest days. From Assisi on to Rome, I mostly kept to it. I decided I didn’t really have much of a choice because of how the towns are spaced and where the mountains and valleys are, though there were one or two spots where I thought I might be able to save a day.

After a rest, I visited the city pinacoteca, then I had a few drinks with some Austrian pilgrims, met some American veterans who were visiting Assisi, and a big group from Indiana. I had dinner with my friend from Colorado and we had a great conversation.

Most of the art in Assisi is pretty old, except for one big thing: the equestrian statue of St. Francis outside the basilica, which is only a few decades old. Lots of people have strong opinions about modern art, but I quite like it. As an American it reminds me of the famous James Earle Fraser statue, The End of the Trail, of the Indian with the spear slumped over his horse. I didn’t get a picture of it, but there’s a copy in Spello and I took a picture of that.

It depicts the moment in St. Francis’s life when he comes home from the war, a defeated man. It’s pretty sobering. When he left, he said he would come back a great prince. But that’s what a man looks like when he’s ready to serve God. To use a metaphor I think St. Francis would appreciate, it’s a statue of the almighty breaking his yearling.

Day 15: Assisi to Foligno, 12 miles

I walked out the Porto Nuovo at six, and walked in the shade of Mount Subasio as the sun was rising behind it. Assisi was wonderful, but I was also happy to get on the road again where it’s a little quieter.

The first conurbation you pass on the way to Foligno is Spello, a beautiful medieval town. I stopped for coffee there and chatted with some Australian bikers. I walked into a couple of the churches and continued on to Foligno.

I arrived in Foligno around 11:30, an early finish to a short, mostly downhill day. Most of the towns you visit are on hillsides, but Foligno is on the plain. As I was standing in the piazza—on one foot, like a flamingo, nursing a blister—a man came up to me and asked if I was looking for something. He was from Missouri, but he lived here. He had married an Italian girl, who was at home, seven months pregnant, and invited me for dinner. He picked me up later that afternoon, and I had a lovely dinner with his wife and mother-in-law in a house outside the city. He offered me a copy of Louis de Monfort’s True Devotion to the Blessed Virgin, and I regret turning it down, but I didn’t want to carry a hardbound book in my pack.

Day 16: Foligno to Poreta, about 15 miles

I left early that morning and arrived in Trevi, about the halfway point for the day, at 9 AM. The Franciscan convent outside of town was closed, so I went to a cafe and had a second coffee for the morning.

Before leaving the Spoleto valley I wanted to stay in one Agriturismo, and the little hamlet of Poreta was a good opportunity. For those who don’t know what they are, they’re rural properties that have been turned into small hotels. They’re very nice. There was some rain in the afternoon, but I managed to get in two hours of pool time—which I had been craving for at least a week—before it started. And I sat in a sauna for an hour. The dinner service on the property was terrific, I had some excellent veal tartare with cabbage and truffle oil, and fried rabbit.

I saw some nice cats on the trail that day, a lot of farm cats, who are often afraid of strangers. There are also a lot of Maremmano sheepdogs, big white fellas who bark at you, but they’re just doing their job, at the end of the day they’re very sweet. The breed is from this part of Italy, and you see them everywhere.

Day 17: Poreta to Spoleto, 10 miles

This day brings you to the bottom of the Spoleto valley, into the city for which it is named. It’s not a difficult day.

I met a nice dog on the way.

Spoleto also sits on a ridge, so there’s a climb up into the city after a mostly flat day of walking. It’s the seat of an old and famous Lombard duchy, though the rocca that dominates the view of the town from outside is much newer than that. I was staying with the nuns at an accommodation below the main part of the town, so I dropped my stuff off and went exploring. A lot of things were closed, but as had become my habit, I went to the main church first, which in this case was Spoleto cathedral.

Spoleto cathedral has three main things to see, after finishing prayers. There’s a letter dated 1222 from St. Francis to Brother Leo, which reads:

To brother Leo, your brother Francis, greetings and peace. I tell you, dear son, as would a mother, that all we have discovered on the way, I will synthesize it briefly in one word of advice so that it will not be necessary for you to come to see me. Here is the advice I give you: whatever way seems to you most pleasing to the Lord God in order to follow him and his poverty, do it. Be sure that by doing so you will receive you will receive the Lord God’s blessing and that you will be in obedience to me. However, if it is necessary for the consolation of your soul that you come back to see me, do come.

The other two things in the cathedral worth seeing are the frescoes of the life of the Blessed Virgin by Fra. Lippi, a very famous work painted on the apse. It has four parts, the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Dormition, and the Coronation. The Coronation, which sits above the other three, is much more colorful than the other ones.

The third thing is the icon of Mary Mother of God, donated to the city by Emperor Barbarossa, which has a chapel dedicated to it.

It was drizzling when I left the cathedral, but I decided to walk up to the rocca anyway, against my better judgment. The drizzle turned to rain, and I turned back around, deciding I had already gone quite a long distance and had nothing to prove. I still felt bad about it, but dinner perked me up. I ate alone that night, but it was one of the best meals of the trip, at the Tempio del Gusto restaurant, where I had four different kinds of tartare and strangozzi with spicy sauce, the closest thing I’ve ever had to a perfect meal. It was cold and rainy; I walked in and it was warm and there was jazz music playing—Spoleto has a famous jazz festival—and the food was even better than the atmosphere.

Day 18: Spoleto to Macenano, about 15 miles

From here, you cross from the Spoleto valley to the Nera valley, which means climbing a mountain. I had already started a bit late, getting on the trail at 7:15 after a quick breakfast at the convent hostel. The guidebooks direct you across the Ponte del Torre, an old Roman aqueduct, which has apparently been closed for several years. So I realized I had to find another way to the mountain on the other side. It meant, after climbing up into the town, climbing back down again to valley level and starting over. Not the sort of thing you want to do early in the morning. It wasn’t a total loss though because the cats of Spoleto were very friendly.

There’s no other way to put it, the climb to Monteluco is brutal. But at the top is a Franciscan sanctuary and a Bosco Sacro dating back to pagan times. Blessed Leopold of Gaiche lived here, a fairly obscure Franciscan who died in 1815 and lived through the chaos of Napoleonic politics in Italy. He refused to join the Napoleonic republic and was imprisoned, but returned to Monteluco later.

I sat in the Bosco Sacro for a little while catching my breath after the climb.

From there you follow ridge lines for about seven or eight miles before descending into the Nera valley. I met another nice cat leaving the sanctuary who was rolling all over the sunny road.

There’s some really lovely walking along here, but I was getting tired by the time came to descend.

In Ceselli, I broke my rule of not stopping for lunch, because I was very tired. It was a mistake because it started to rain, and I had to do the last four miles to my accommodation in a thunderstorm, almost cowboy-walking because the insides of my thighs were starting to look like something you’d teach in medical school. The Nera valley is very beautiful, lots of stark rocks on either side.

It was a holiday weekend in Italy and most of the hotels were booked up, so I had to try pretty hard to find a bed for the next several nights.

Macenano, where I stayed that night, is a very small hamlet, with only one or two accommodations. But dinner was good, and I relaxed for the afternoon and read Chesterton’s biography of St. Francis and thought about it for a while. I’m interested in how he compares St. Francis to the tales of Uncle Remus, there’s a similar spirit in Fratello Lupo and Br’er Fox, and it’s something he noticed.

Day 19: Macenano to Piediluco, about 13 miles

This day’s walk is full of Sister Water, “humble and useful and chaste,” the first stretch along the Nera, followed by the Marmore falls, and ending in Lake Piediluco. The valley has steep walls that make for a dramatic landscape.

In the next town down the Nera, there is a somewhat well-known mummy museum, but it wasn’t open when I passed it, and I wasn’t going to wait around. I did stop for coffee though, and a nice Italian man buying a pack of cowboy killers started talking to me in German—a lot of people did that because of how I look—and I had no idea what he was saying. There was a nice, slightly ragged cat in the square.

You have an option, once you get close to Marmore, to climb straight to the top, or view the bottom of the falls and climb through the park, paying an admission fee of 10 Euro. The climb is a little difficult either way, so you might as well get a good view. The Marmore falls, if you haven’t heard of them, were built by the Romans—the largest manmade waterfall in the world. Cicero and Varro debated in the Roman Senate about what to do with the swamps around Rieti, and the falls were the solution. They’re very beautiful.

From Marmore, you walk along a drainage channel to Lake Piediluco. The town along the lake is very beautiful too. The main church in town, from the 14th century, is dedicated to St. Francis, because he stopped there on his travels many times. It contains a relic of him. I stamped my credential there and lit a candle in front of the relic. Outside the church a lady told me to pray for peace in Rome, and I told her I would.

The lake wasn’t there in St. Francis’s time, but it’s lovely today. It was raining so I wasn’t able to go to the beach, but it’s the sort of place I could imagine spending a vacation.

I had dinner at a Sicilian restaurant in town, specializing in seafood, the first I’d eaten on the trip so far. It was delicious. One of my favorite things about dining on this trip is how, when I would order a lot of food, the servers invariably smile, with a look that says, “oh, that guy’s here to eat.” Italians are, of course, famously proud of their food, but you really see it in moments like that.

Day 20: Piediluco to Poggio Bustone, about 14 miles

Today is the last real climb of the trip, into the Rieti Valley with its four Franciscan sanctuaries, crossing over into Lazio. There was mist over Lake Piediluco when I left at 6:30, and I couldn’t see the mountain yet. I stopped for coffee most of the way up the mountain at 8:45, and got the first views of the Holy Valley around 9:15.

The Rieti Valley is incredibly beautiful. Over the next few days we had a lot of rain, so I didn’t get as good views as this first day, but the views I did get were extraordinary.

At about 10 AM I reached the Faggio di Francesco, St. Francis’s beech tree. The story is that he lied down here, and the tree wrapped him up like a little baby. Supposedly it isn’t the same tree as the one that existed here. Whether or not you choose to believe so, it is an extraordinary tree, it looks like a bonsai, with the gnarled trunk and the way it flows down the mountain.

From there it’s a few miles downhill to Poggio Bustone, and the first of the four sanctuaries in the valley, San Giacomo (St. James in English). Poggio Bustone is a very vertical city, so much so that a map from above doesn’t really give you a good sense of the place. I arrived at the sanctuary at 12:45 and asked the friars if there was a priest on hand to whom I could confess my sins, but nobody spoke English.

I walked through the gate beside the main church looking for water, and found a group of pilgrims sitting at a table, led by a Franciscan friar who didn’t live there. He pointed me to the water. The other friars told me they were booked up for the night. So I checked out the church and went down the hill to my accommodation, but not after petting the nice big dog, and admiring the two beautiful gray churchyard cats, one with medium hair and one with short hair.

St. Francis famously addressed the people of this town with the greeting “Buon giorno, buona gente,” or “good morning, good people.” But its main association with the life of St. Francis comes from the story in which an angel appears to him and reassures him that his sins are truly forgiven, a moment depicted inside the church.

It was a Sunday, so the friars told me Mass was at 5, so I walked down into the town to rest until then. I had some language issues with my hosts, but absolutely no complaints about the BnB, which was lovely, and a great deal for a whole apartment at 35 euro. I was in the shower with my clothes in the other room, fully expecting to luxuriate for the next few hours in an edenic state and dry out my thighs, when there was a knock on the door, followed by the sound of the door opening. I did not want to offend them with my nakedness. But when I ventured out, there was nobody to be found, but a plate of pasta faggioli on the kitchen table. Clearly the intention was for me to eat it, so I did, then lied down. Then there was another knock on the door, and the same lady had come by again with some fruit. They were really taking care of me. I ate the apple but wasn’t feeling up to the task of peeling a kiwi.

I returned early enough to sit in a couple of the gardens they have, and look at more cats. This sweet little guy wanted to go to Mass, he was walking right through the front door.

He started to get scared of a few congregants arriving for the evening’s service with their dogs, so I picked him up. That was a mistake, because he scratched my face and drew blood. They sang a hymn to an English tune at the beginning of Mass.

Afterward I walked back down to the town again for a drink and dinner. The lady who ran one of the handful of establishments in town asked if I wanted anything to eat. I told her I didn’t want to offend her, but I was going to eat at an inn further down the hill. She said it didn’t offend her, because her grandmother owned it. There had been sporadic rain all day, so views weren’t as good, and I went to bed early.

Day 21: Poggio Bustone to Rieti, about 11 miles

I left Poggio Bustone at 6:30, passing through Cantalice that morning. It’s the hometown of St. Felix of Cantalice, the first Capuchin saint, and there are some murals of him there.

On the way out of the town a nice tortoiseshell cat followed me for a little ways after I scratched him a little.

Views of the valley were not as good because of the weather, but the fog made for some nice visual effects.

I arrived at the bottom of the hill below La Foresta at around 9:30, when it started to rain very hard. There was a pilgrim hostel for which I didn’t have any kind of reservation, but I walked through the gate to see if I could wait out the hardest of the rain. There were a lot of animals in the yard—some geese, chickens, a couple of cats and a big dog. The lady who ran it said I could wait there, let me inside to her sunroom, and made me a coffee and gave me some cookies. As I waited for about an hour, her longhaired cat kept coming inside, looking at me, coming close then backing away, doing that coy thing cats sometimes do. The lady said I didn’t have to pay for the coffee, but I left a few Euro for her anyway when I left. There was a break in the rain, so I continued to the sanctuary, the second of the four.

They claim in Assisi that St. Francis composed the Canticle of the Creatures there, but it’s also claimed that it was composed here. I don’t know who’s right, but at this point I had them both covered. The other remarkable event in the life of St. Francis that occurred here is the miraculous harvest of grapes. I sat in the church for a little while.

I had noticed from the first few days of walking one of the major contrasts with the Camino de Santiago, but it’s especially apparent here: that the churches are much simpler than in Spain. In Spain, I’ll never forget walking into the church in Navarette, with an enormous gold altar dozens of feet tall. You won’t find that here. These Franciscan sanctuaries especially are quite simple.

It started raining again as I left La Foresta, but I walked anyway.

I arrived in Rieti around noon and slept until 2. It’s the largest town in four or five days, and also at the bottom of the valley, not on a hill. I stayed at a hotel right by the cathedral, where my room had a nice view of the gap in the mountains I would pass through, after a rest day, on the way to Rome.

Rieti was an important city to the Sabines, and it’s where Varro was from. It’s also known as the umbilicus Italiae, or the bellybutton of Italy, because of its central location. I explored the city until 5:30, visiting the cathedral and a couple of other churches, then sat in the garden to think a bit.

I had a difficult decision to make. My initial plan had been to not really rest the following day, but to leave my pack at the hotel, and walk the 15 miles to Greccio, passing by Fonte Colombo on the way. If I did that, I could see all four sanctuaries. On the other hand, my right foot was bleeding, I would have to take a train back from to Rieti from Greccio, which sounded a little dodgy, and I had some longer days on the Lazio plain I probably needed to rest for. So I decided to just take the next day to see Fonte Colombo, and do three out of four. A difficult decision, but you can’t do everything.

I had also been thinking about an overarching prayer intention to dedicate my trip to, and I decided that afternoon to pray that the pope would meet with the Dalai Lama. So far Pope Francis has demurred about this, with people around him suggesting the diplomatic situation with China is too sensitive. I think it’s a pity to let the pope’s visitations be dictated by the whims of the Chinese Communist Party, and in the interest of the freedom of both West and East, I decided that was a good thing to pray for. The Dalai Lama has said St. Francis is a model of Buddhist monasticism as well, and perhaps the saint whose name the pope has taken could help bring them together.

I went for a beer by the river, then had dinner and went to sleep.

Day 22: Rest day in Fonte Colombo and Rieti

I got up at 7:30 and had breakfast at the hotel, then started walking out to the sanctuary a few miles West and up a hill. When you’ve been walking with a pack for about three weeks, then walk without one, you feel like you’re flying, and I made very good time. Fonte Colombo is important to the Franciscan story for two events: it’s where St. Francis had his eyes operated upon with the help of Brother Fire, and it’s where he wrote the Franciscan rule.

On the way up I encountered one of those funny dogs who, despite being very big and strong, are very afraid. I tried to pet him but he hid behind a cart and looked at me sheepishly.

I arrived at the sanctuary around 9:30, and a friar was explaining some of the art inside the church to some guests. I’m glad I had time to take in Fonte Colombo slowly, because it was my favorite of the sanctuaries I had seen so far. There’s more there. Approaching from the south you see the actual fountain the sanctuary is named for.

There were lots of cats up there, including this pretty grey one.

Behind the main church are a series of chapels and the Sacro Speco, much like at La Verna. There’s the cell where St. Francis wrote the Franciscan rule, which is full of little notes and mementoes from pilgrims who have passed through.

In the chapel of St. Michael the Archangel, there’s a copy of the Franciscan rule hanging behind the altar, and when I got there a little wren who had let himself in to praise God was sitting on it.

Beneath the St. Michael chapel is Francis’s grotto, and beside it is another belonging to Brother Leo. I checked it all out but was a little worried that the poor bird might not be able to find his way out again, because he had started flying around, seeming to be in some distress.

So I walked back up to the cloister, where a woman was arriving to help the friars with something. I told her I was worried about the bird. She communicated that to someone inside the cloister, and a handyman came out, and I showed him that the bird was still in there. He told me not to worry about it. Satisfied that someone had their eye on it, and that it was no longer my problem, I sat in the woods for a little longer admiring the place, then walked back to Rieti.

Back in Rieti, I tried to visit some museums but they were mostly closed. So I paid a visit to the home of Margaret Fuller Ossoli, an early American feminist who lived here in the 19th century. Hester Prynne is based on her, and her book Women in the 19th Century was quite a sensation. Edgar Allen Poe had a withering line about it, saying it’s a book few women could have written but none would have published.

Day 23: Rieti to Poggio San Lorenzo, 13 miles

From here begins the final leg to Rome. The last two days of walking, you’re in an outer suburb of the city, then an inner suburb, so there are only a few more days of rural landscape left.

I started out around 7:30, and the fog began burning off by about 9, for a pretty nice day of walking. There was a lot of walking through high, wet grass, and my clothes got soaked.

By 10 AM I had five miles to go. One of the local sheepdogs came out to see me around then.

He walked with me for about a half mile, before he got tired of climbing the hill. He was very nice, he walked ahead of me, then looked back to check how I was doing. I thought I heard what sounded like a boar in the bushes, and maybe the dog was aware of it and that’s why he was escorting me. I don’t know, but it was nice to have a companion.

There was an inexpensive agriturismo in San Lorenzo, so I stayed there. I arrived around 11:30 and checked in. They told me the only lunch to be had was in town, and not feeling like walking the mile to the only cafe, I skipped it until dinner and went swimming in the pool.

Some of the agriturismos are very fancy, this one was a little more humble, but still very nice. I’m sure there are some people that would find it strange to swim in a pool next to a flock of geese and chickens, but I enjoyed it. As I was sitting there, two ladies from California and Texas arrived, and I chatted with them and we had dinner that evening. The food was great, buttered ravioli with sage, and one of the best pork chops I’ve ever had.

There was a cat there too.

Day 24: Poggio San Lorenzo to Ponticelli, about 14 miles

Got on the trail at 6:30—no breakfast at the agriturismo but they’d given me a little receipt for a coffee and pastry at a bar in town, so I was able to eat something on the way out. My feet were still blistered, but I was keen on walking in sandals, so I slapped Compeed all over them.

At around 8:30 I lost the trail for the first time on the journey. I was trampling through a field of high grass, looking for a stream crossing. Between the field and the stream was a hedge of thorn bushes, and I kept looking for a break in them that I could go through. There wasn’t one. It was the sort of moment machetes are made for. Right when I was considering barreling on through, I stepped on some cow bones, and took it as a sign that I should look a little more carefully. So I retraced my steps, and eventually found the trail again.

After ascending one hill, there’s the romanesque church of St. Victoria, where I sat and drank water for about 20 minutes. The building was closed so I couldn't go inside.

There was a flock of sheep blocking the road at around 11:50, and they made way for me as I approached. This clearly upset their guard dog, who barked at me.

I made it to Ponticelli around 1, the last evening in the Italian countryside—the other towns from here on out are pretty big. There was nowhere open to eat lunch, so I waited for the gas station/bar to open and watched some tractors drive up the street. At 4, I ate some ice cream and had some coffee. The local church was pretty simple, but they did have a few nice frescoes: St. George and St. Francis receiving the stigmata, and the pulpit had a painting of the harrowing of hell that I enjoyed looking at. I had dinner again with the American ladies, and we had some good conversation.

Day 25: Ponticelli to Monte Rotondo, about 18 miles

This is the last serious day of walking on the trip. I woke up at 5:40, and the bar opened for coffee and breakfast at 6. During this stage you’re very much on the plains of Lazio, and you can see flat land for long distances, and you start to get some views of the outskirts of Rome.